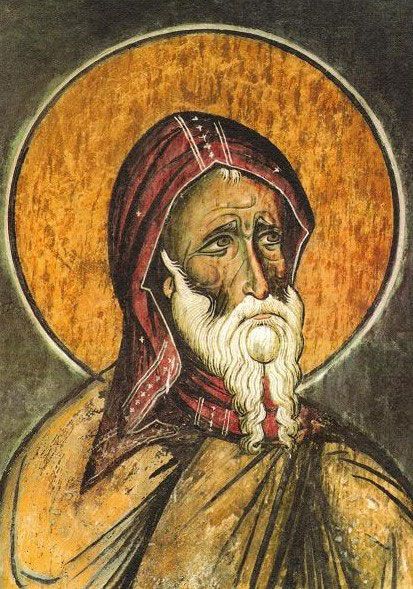

Saint Ulphia

(died January 30, 776)

Icon available on

UNCUT MOUNTAIN SUPPLY

Click HERE to purchase

I started writing this post in January but was dealing with the aftermath of a terrible fall that hurt both knees badly and caused me to slow my movements even more than what is typical, so it became lost for some time and I am just now getting back to it on February 6th. I will try to post it in the proper order online, but if I am unable to do that, I know you will understand.

There are a surprising number of female hermits who have been sainted. Typically, when the subject of "hermits" comes up, most folks tend to picture a grizzled old man, usually with long, unkempt hair and a beard to match. For some reason, the men get a lot of celebration while the women see very little mention. Perhaps women are more successful in remaining hidden.

I enjoy reading about these female hermits, searching for clues as to how they survived this mode of life and hoping to get some picture of their inspirations and motivations. I wish there was more information on-line. This is yet another one of my many projects for which there is not enough time. The balance between the religious, intellectual, and writing projects is delicate. There is only so much time in each day, and I am becoming less and less able to do much of anything physical, while at the same time I have, essentially, no help with any of the physical jobs that need doing in order to function properly.

Today's little-known female hermitess lived near Amiens, France, in the 8th Century. She was a disciple of Saint Domitius, located at the Abbey of Saint-Acheul, in Amiens. Perhaps her relationship with that (male) saint is how she became known by others and how a community of disciples began building hermitages around her. She organized them into a community and then went back into seclusion.

It is that particular sequence of events, when she got involved with organizing others, that initially interested me, particularly because I am currently peeking outside my own hermitage in a temporary effort to offer some inspiration for a type of ministry that I feel the Church is lacking, as a whole. (This is the "Parish Membership Ministry" that I've designed with various modules, including the "Elder Orphans" ministry. It is taking forever to even see if it will be enacted because it is proceeding in that glacially slow way that appears to be so typical of the churches that are struggling to keep their membership. They are so stuck in their procedures that I believe they have trouble letting go of those things that are bogging them down to begin with. The infections of modernism and secularism are at the heart of most of it. More about that in another post.)

I have encountered many unexpected surprises in my brief foray into a recently increased contact with other humans. Other people, not realizing that I am living a different kind of life than they might imagine, are not equipped to understand our differences.

In the Middle Ages, I have the impression that most people were aware of the vocation of hermit and anchoress.

I have considered wearing a modified uniform, a "habit" that communicates some kind of religious lifestyle but which is different enough from the standard habit that I won't look as if I am impersonating a nun or sister of any particular order. The key point is modesty, of course, and a simple style. My style has leaned toward maxi dresses since I was 15 and I used to sew them up by hand from the lightweight cotton Indian 'bedspreads" that were popular during the hippy era. I have a bolt of nice, plain linen I bought online and will likely end up sewing some new ones with long sleeves, and leave it at that. Somehow I have to get the back room organized in order to produce anything with that sewing machine. When the time is right, The Lord will provide the needed help.

Up until now, I have liked keeping a low profile and not catching the attention of those around me. However, I am beginning to think that it may be time to have more of an outward presentation and to start wearing a habit of some sort. It would certainly reduce the number of pieces of clothing that I keep in the hermitage and would, among other advantages, reduce the amount of laundry duties. It would also explain to some people, without my having to say anything that could be interpreted as rejection of others, that I am not typically involved in the normal entertainments of secular life.

Saint Ulphia sounds like a real character. Supposedly, she was living on the banks of the Noye River, determined never to marry, and when potential suitors came to bother her, she would behave as if she was crazy, just to scare them off. The Bishop gave her "the veil" when she was 25, I suppose granting her similar vows to that which the Diocesan hermits take in these modern days.

She was the attendant of the famous hermit Domitius, who was a Deacon who gave up active work for the life of a hermit. He was much older than she was. She attended to him, and he endowed her with his wisdom. It is not unusual for hermits to attract devotees who learn from them the wisdom of the vocation. It reminds me of my experiences as a Hindu nun, under the tutelage of Swami Swahananda at the Vedanta Society in Southern California.

I do not have a teacher for the last 20 years, but having experienced the support of a highly spiritual elder in my former religion, I feel that I have at least the confidence to try to be a decent Catholic hermit.

There has yet to be a reputable Catholic guide and exemplar for me, ready at hand, and I am sure The Lord would provide one if He felt this was necessary. He knows how reliant I am upon the writings of the experts and I will not get waylaid by quacks or charlatans who try to bamboozle the unsuspecting devotee through thaumaturgic "cosmic poo poo." He knows that I stay grounded.

There has yet to be a reputable Catholic guide and exemplar for me, ready at hand, and I am sure The Lord would provide one if He felt this was necessary. He knows how reliant I am upon the writings of the experts and I will not get waylaid by quacks or charlatans who try to bamboozle the unsuspecting devotee through thaumaturgic "cosmic poo poo." He knows that I stay grounded.

Speaking of which, I have received no return phone call from the Archbishop since I reached out in December. I was told in December that he would get back to me around January 13, as he was busy until then. I have followed up with phone messages and another email, and I hear crickets.

I cannot pretend to know the reason(s) why "ghosting" people has become a thing that everyone seems to do when they have no use for you.

But I am aware that I am unimportant and also have no money - so why should anyone respond? I am of no use to them and therefore everything that comes across an Archbishop's desk is automatically more pressing than my needs. Besides which, a Dioscecan hermit's vows are given directly into the hands of a bishop, and it may sound like extra work to a man already weighed down with many weighty matters.

On the other hand, I have already lived this life for 20 years, and the only thing I lack is spiritual support and the ability to retain the Blessed Sacrament on my own personal shrine. I will continue to live this life, God willing, for as long as I remain on earth, and I trust completely that The Lord will give me everything I really need.

I am currently not regularly receiving the eucharist, however, and I do need to rectify that situation. The lady that was bringing it to me was subjecting me to a terrible angry temperament, and yelling at me quite a bit - both here and in her car during errands - also yelling at the other drivers in an unending litany of surreal conversation with people who I doubt could hear her with her windows rolled up. Once she even got out of the car, in the middle of traffic, and walked to the car BEHIND us so that she could yell at the driver. It was a frightening series of events.

I finally could not endure it any longer and I believe it is safer not to have her come here because I am beginning to think that she may be suffering the onset of some kind of dementia, alzheimer's disease or something like it, and there are certain instances when those experiencing this illness have completely lost their tempers and gotten violent. I am not able to run away from her, if she should really come unglued, so I told her not to come here any more.

The deacon did not believe me, I don't think. Or he did not want to. I am not sure what is going on there, but he indicated he would not be making any effort to get me someone else. He muttered something about not having volunteers and how rare they are since Covid. Even after Covid has mostly gone away, people have not returned to volunteering, which I find sad.

The deacon did not believe me, I don't think. Or he did not want to. I am not sure what is going on there, but he indicated he would not be making any effort to get me someone else. He muttered something about not having volunteers and how rare they are since Covid. Even after Covid has mostly gone away, people have not returned to volunteering, which I find sad.

I also wonder why no one at the parish makes any effort to reach out for volunteers and perhaps announce them after mass. So many Christians are in need of companionship with other friends of Jesus! My "Parish Membership Ministry" is designed to help with this issue, but I despair of it ever getting off the ground. Ever since the internet became enmeshed in our lives, it feels as if humans are no longer interested in interacting with other humans at all.

If I can find someone to drive me, or somehow get a car, it may be better to go to church instead of having someone come here, even if the pain of this exercise is extraordinary. The arthritis I inherited from my mother's side of the family is fairly awful, but I look upon it as an ascetic practice, so even if there is a lot of extra pain, I think I will accept if someone offers to take me, and I will work hard to try to get SOME kind of vehicle, since getting transportation is an awful ordeal at present.

Something tells me that it is beneficial to the spiritual constitution to be treated with disdain. Jesus was treated with actual contempt, scorn and ridicule, yet he managed to maintain his modesty and gentle demeanor throughout his entire ordeal here on earth. I must do the same, to the extent I am able. I am really working on my patience, at present. Being in constant pain for 20 years has added to the difficulty.

Despite it all, I continue to live my hermit life, praying unceasingly, with my mind on Him throughout the day, relying upon the many examples of hermits through the ages in order to form my holy vocation.

I pray for you, as I hope you pray for me.

May God bless us all.

Silver Rose